Written by: Anna Redly

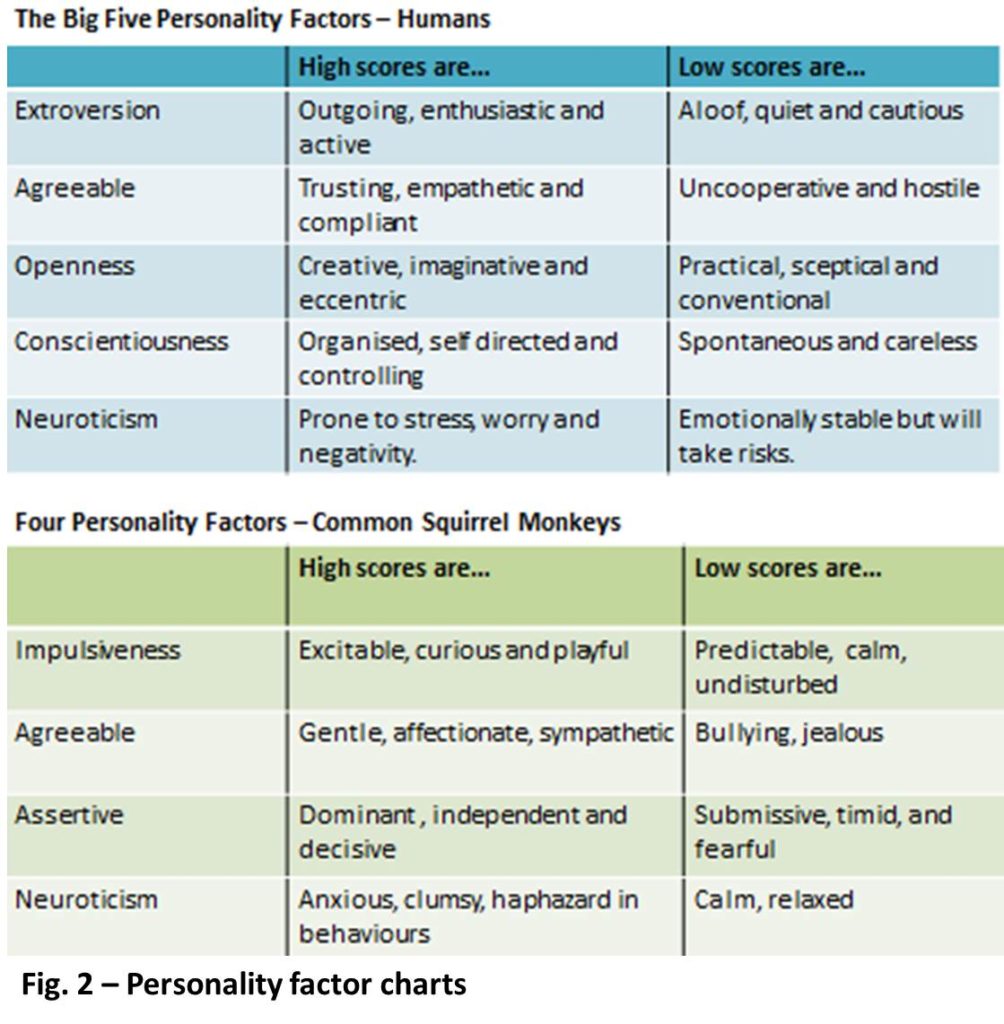

A recent study comparing the abilities of 4- to 5-year-old children and the Living Links capuchins found that only the human children were able to make predictions using abstract knowledge.

Imagine that there are two brown paper bags in front of you. You know that they contain sweets, but not what kind. You reach into the first bag and pull out a handful of four green gobstoppers. You then reach into the second bag and draw out four chocolate buttons. After just taking four sweets from each bag, you can make a reasonable prediction about what kind of sweet you might find if you went in for seconds in either bag: a green gobstopper for the first bag, and a chocolate button from the second bag. This is called a ‘Level 1 Abstraction’. You will also likely arrive at the conclusion that brown paper bags contain sweets of the same kind – this is called a ‘Level 2 Abstraction’. You would only need to take one sweet from a third bag to predict that all the other sweets in the bag will be the same kind.

Abstractions represent generalised information that is common across different situations, like in the sweet example. This ability is central to the way we humans navigate the world, helping us to learn quickly from limited information and make predictions in new situations. The questions that Felsche and colleagues wanted to investigate were how early human children develop this ability and whether it is an ability that we share with other primate species.

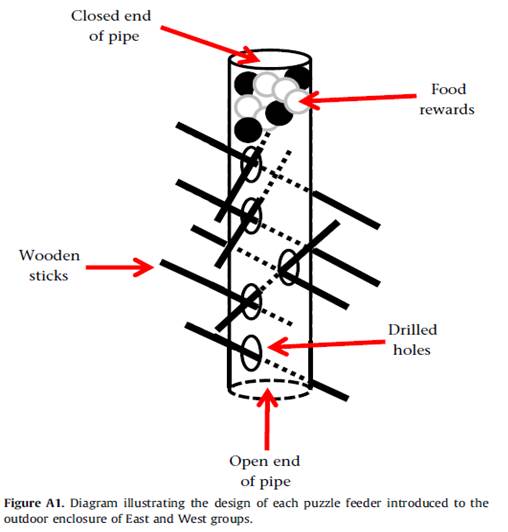

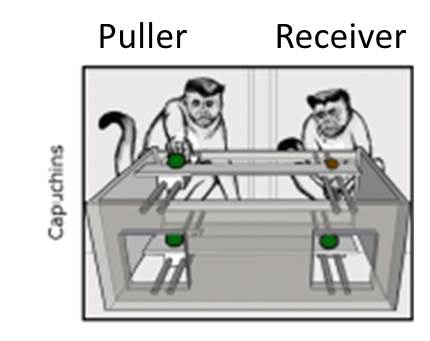

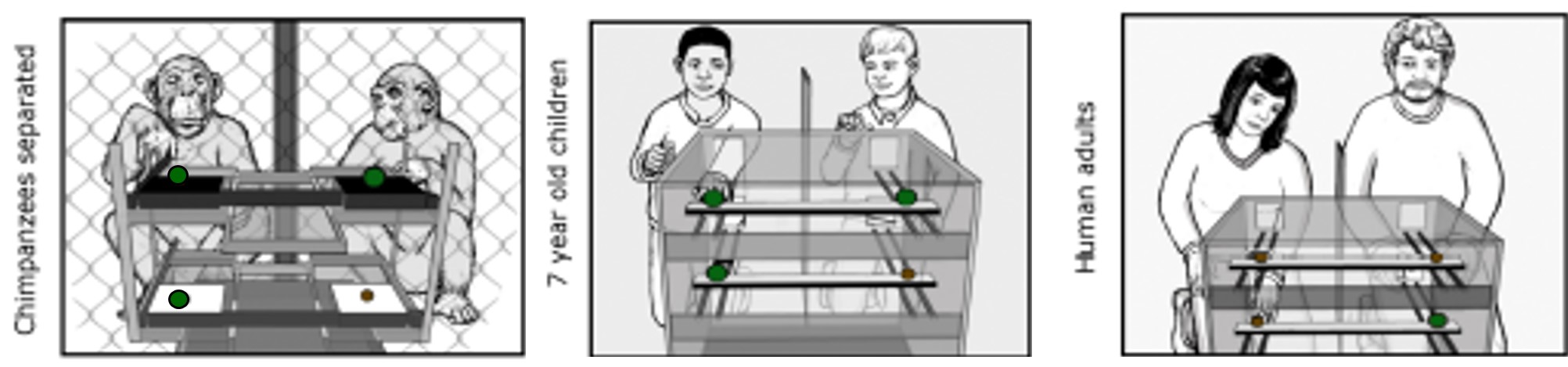

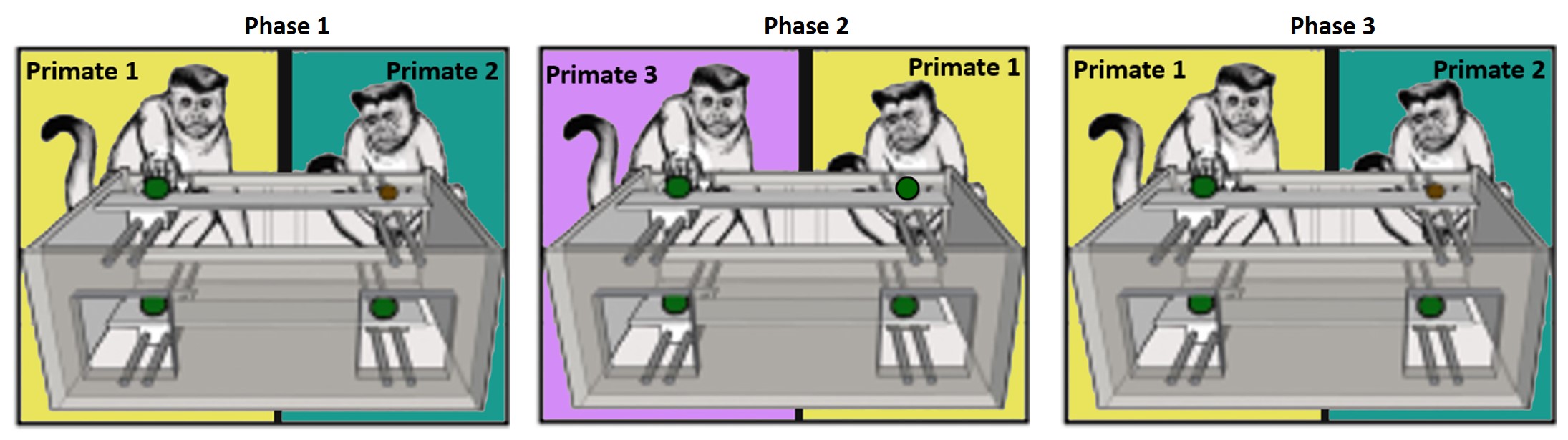

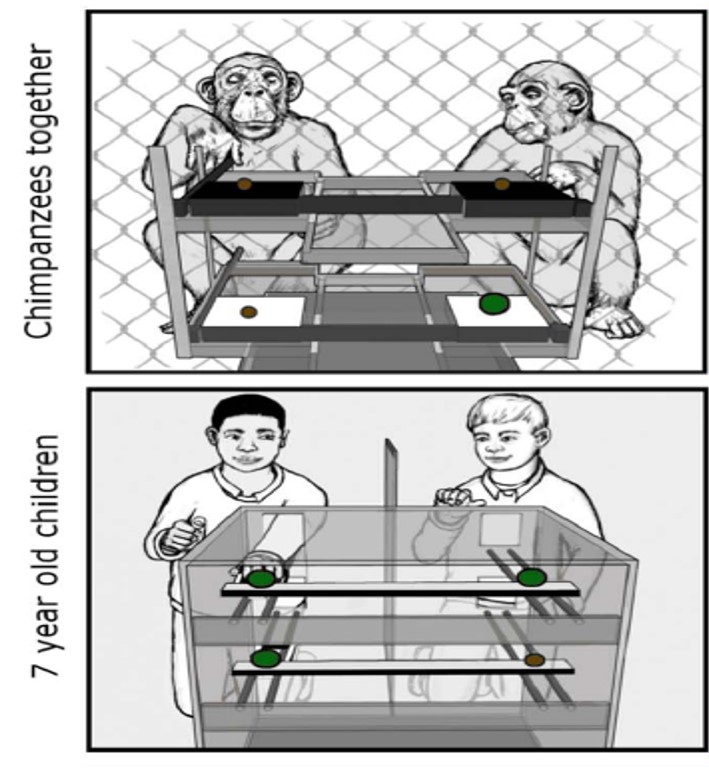

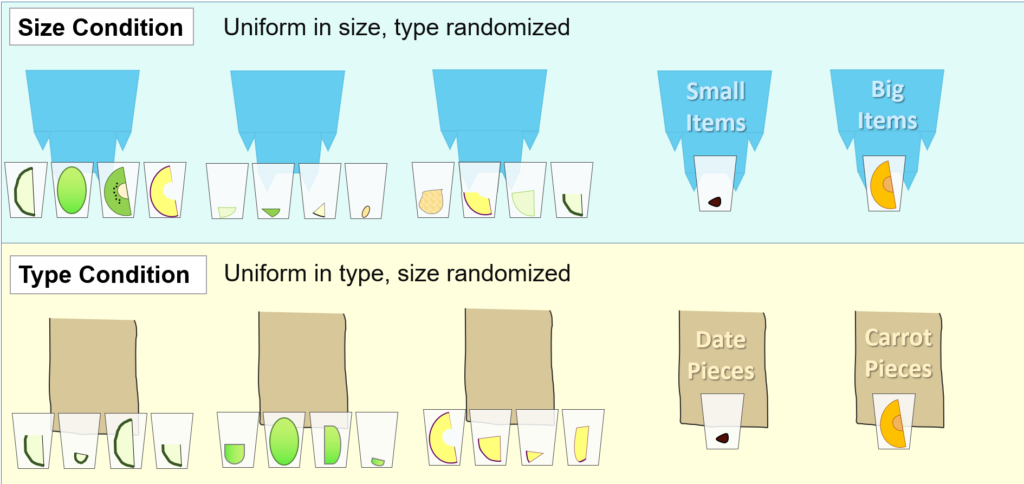

To explore this question, Felsche and colleagues designed an experiment with a similar principle to the sweet example. The researcher would sample items from three containers, which contained sticker strips for the children and food for the monkeys. There were two experimental conditions. In one condition, the sampled items supported the idea that items were sorted into containers by their type (e.g., four apple pieces from one container and four raisins from another). In the other condition, sampled items suggested that items were sorted into containers based on size (e.g., four small items of different types from one container and four large items of different types from another). After exposure to one of the two conditions, the participants were then presented with two new containers and an example item from each and were prompted to choose from which container they wanted to receive their next item.

In both conditions, the two example items were always a small but high-value item from one container, and a large but low-value item from the other container. The prediction was, that when the children and monkeys were in the type condition, they should choose the next item from the container with the high value example item – so that they can get a high value item too. In the size condition, one high-value sample does not guarantee that the rest of the items in the container will be high-value, as items are sorted into containers based on their size rather than type. If the participants recognised this, they would choose the large and low-value option because no matter which food type will be next, they at least can secure another big item, which is always better than a smaller one.

The researchers found that the capuchins choices of test containers was at random and not influenced by whether they had previously seen that treats are sorted into containers based on their size or their type. This performance suggests that the monkeys did not learn about the abstract rules determining food distribution patterns across containers. The children, however, chose the hidden sample linked to the small high value item more often in the type condition compared to the size condition. This sensitivity to the experimental condition suggests that the children were able to generalise at the second level of abstraction and make predictions accordingly.

The researchers then designed a second experiment, to see if the capuchins were able to form Level 1 Abstractions within this paradigm. In this experiment, like in the sweet example, the monkeys and children were presented with only two containers from which four evidence items were sampled, respectively. Like in experiment 1, there were two experimental conditions (type and size), but this time the choice items were sampled directly from the original containers, so no generalisation to new containers was required.

Again, the capuchins performed at chance level in both conditions, suggesting that they are unable to form Level 1 Abstractions. The children performed above chance in the type condition, but seemingly at random in the size condition. This is interesting, implying that while children can use Level 1 and 2 Abstractions to inform predictions, this ability might depend on the item characteristic they form generalisations about (e.g. type or size). However, the researchers also ran a computational model based on the children’s and monkeys’ preferences. This model suggested that the children’s above chance performance in the type condition could be due to the fact that they simply cared more about their reward’s type than its size.

This study has extended our current knowledge of abstract knowledge formation in non-human species and provided a novel task design that can be altered to learn more about the abilities of different species – both contributing to the investigation of whether humans are indeed unique in our ability to use abstract knowledge.

Want to know more? Click here to read the paper!

What is Living Links? Click here to learn more.