Written by Dr Emma McEwen

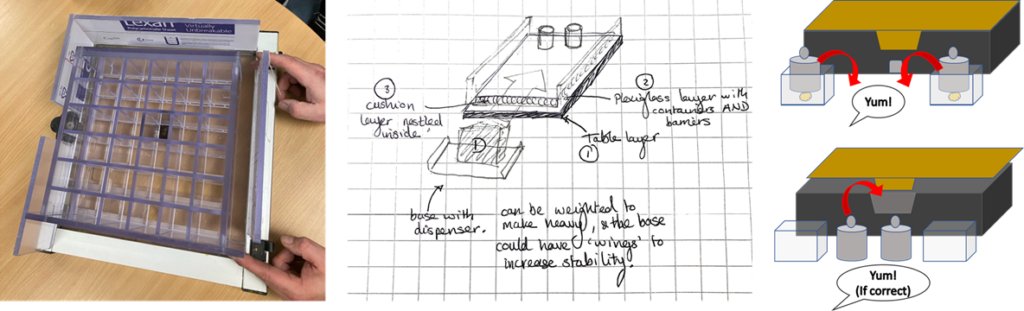

In many of the experiments at Living Links we use physical apparatuses that the monkeys can interact with, like different puzzle boxes, enrichment containers, dispenser shoots or objects for them to explore. When we design these new apparatuses, there are lots of different considerations we have to be aware of, and its often a collaborative effort between the researcher, the keeper team, and our Psychology & Neuroscience workshop to come up with the best solutions!

Our primary concern is always the safety of the monkeys, and of the experimenters. We always have to consider that a material is safe for the monkeys to touch in a way that they can’t get hurt, is non-toxic and easily cleaned so that it’s safe for their food rewards to touch, and something they can’t pull into their enclosure and do damage with.

Secondly, it has to be durable – capuchin monkeys can be stronger that you might think! We always have to consider the durability of the materials we use, making sure they can’t be easily torn or snapped, and that the monkeys can’t knock them off the experimenter’s table.

It also has to be enjoyable – we always want our research sessions to be enjoyable experiences and only positively reinforce behaviour. This includes only using materials and apparatuses that the capuchins enjoy interacting with. Sometimes, it can be difficult to predict whether they will enjoy touching certain materials. For this reason, we sometimes run some taster sessions, called pilot sessions, to offer the monkeys a chance to interact with a material or part of an apparatus before we build the finished product.

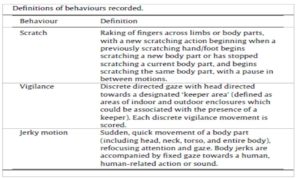

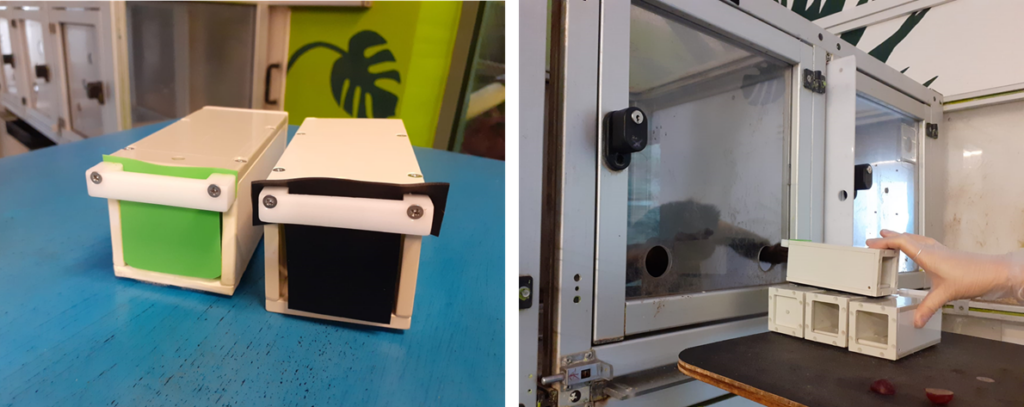

For example, myself and my collaborator Andreea Miscov are currently testing two types of material to be used as potential ‘flaps’ for a grid box the monkeys will need to search for food rewards in, as part of a memory experiment. One is a silicone material and the other a harder plastic material. There are often individual differences between monkeys, and while some of the monkeys have no problem touching the silicone material, others have not wanted to! On the other hand the plastic material seems preferred from pilot testing so far. It can be important that there are no major differences between how the monkeys interact with apparatus, especially with experiments looking at time measures (a monkey less keen to touch an area of the apparatus will take longer to get their food reward!).

Video example showing durability test, prototype flap box and piloting with the monkeys!

Last but not least, it must be practical – for the designs of our experiments, we need our apparatuses to function in particular ways such as hiding food, sliding things into other things, moving in certain ways, or having certain weights. It can sometimes take us lots of time and trips to hardware shops to browse different materials and find the one that functions or moves in the exact way we’ve dreamed of when designing the experiment!

It can be very challenging to find something that fits all these criteria, but it’s a fun problem to solve!